‘How do we make decisions for children during an emergency like COVID 19?’

Perhaps, not surprisingly, this is the number 1 question we’ve been asked recently.

It’s a very hard question to answer, especially when we know your aim is to do the best you can for the children you’re protecting and caring for. Often, the dilemma goes something along the lines of:

How do I ensure my work is of safe standard when I can’t visit the child or family, have cases needing decisions immediately, and resources that are even more limited than usual?!

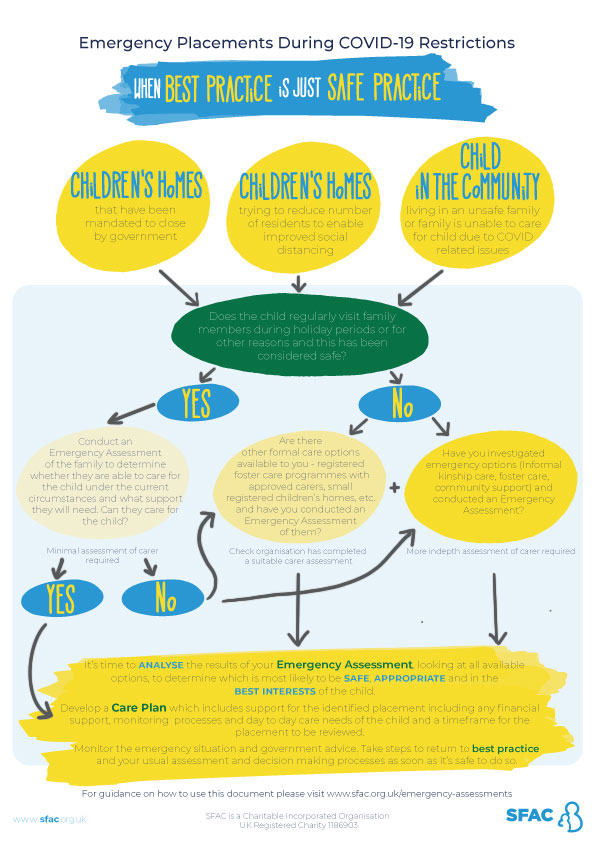

There have been a lot of resources released recently hoping to provide some support in this area. Having looked through many of them, we realised there seemed to be a gap when it came to brief, practical strategies organisations can implement immediately. We hope the following decision map and accompanying guide to making decisions about where and how to place a child during a large-scale emergency, like the COVID-19 pandemic, helps fill that gap.

Confident readers of English should get through all of it in 15 – 20 minutes – unfortunately, putting it into practice will take a bit longer than that!

Managing expectations in emergencies

Before we go any further, we want to make it very clear that during a large-scale emergency like a pandemic or immediately after a natural disaster, our goal changes. We’re no longer aiming for ‘best practice’. Instead we’re going for ‘the safest practice within current limitations’.

It’s important to remember in the midst of a crisis ‘good enough’ really is good enough.

Emergencies are tough; emotionally, physically and professionally. We face limitations in what we can do and have to take bigger risks. Our day to day practice has to be different from our normal processes. That may also mean it’s different from what we want to do.

The combination of change, uncertainty and heightened risk also means our baseline stress levels, our starting point, are higher than normal. We may feel scared, anxious, and worried about children we are unsure are safe. We might be anxious and worried for ourselves. We may feel frustrated we can’t do more. Emotions and experiences will vary from place to place and person to person and even within individuals on any given day but everyone will face periods of challenge and stress throughout the emergency period.

A change of focus: moving from “best practice” to “safe practice”

Our primary focus during times of crisis has to be basic needs – food, water and safety. Ultimately, this means organisations need to change their assessment processes to focus on these core needs and prioritise their cases accordingly. In crisis mode, cases we might normally respond to very quickly may have to be put on a waiting list as more pressing cases (life or death situations) take priority. Safety and survival are paramount.

Usually, our work at SFAC involves equipping our partners to protect and care for the children they work with in a way that allows them to not just survive but to thrive. In times of crisis, however, the focus flips from thriving to surviving. From “best practice” to “safe practice”.

The decision map below and the explanation and guidance that follows are designed to help you work through the process of assessing and finding appropriate placements during this pandemic or similar, large-scale emergencies. They relate to decisions where you (and your organisation) believe a child needs to move in order to be safe and where restrictions arising from the emergency situation are limiting the services you can offer. We are grateful to have had the assistance of Joseph Luganda from CALM AFRICA in Uganda in developing this for you.

You can instantly download a printable copy of the decision map by clicking on the image. Alternatively, you can download a full pdf booklet including all the information in this post, the decision tree and some examples of Emergency Assessment forms from our Free Resource Library.

Sign Me Up for the Free Booklet!

You can access all the resources in the library by joining our Subscriber Club. We recommend this option as the booklet contains additional resources and information, you’ll have access to the other resources in our growing library and we’ll also follow up with you to see if you would like any further assistance or have other questions.

Some things stay the same

- In all circumstances, day to day and during emergency situations, we must first work with government officials and processes. This includes informing the appropriate authorities of any actions and decisions you’ve made.

- In all circumstances, even during large scale emergencies, the first response is always to try and resolve concerns, meet needs and lower risk without moving the child to a new placement (carer/children’s home/family member etc.).

For a family struggling to provide basic needs such as food and water, the first priority is to explore how to meet those needs. It is not to move a child.

Where there are concerns about a child’s safety the first response is to ask:

“Can we support the family to improve the situation and lower the safety concerns?”

However, during widespread emergencies, the available support is likely to be more limited which will have consequences for determining which cases you prioritise, the support you offer as an organisation and when you may make the decision that the child needs to live elsewhere.

Large scale emergencies mean there will be children’s homes, foster carers, kinship carers or even parents who are usually able to care for children but can no longer do so. This may occur for a variety of reasons related to the nature of the emergency. For example, at the moment, carers may have contracted the virus or and, as a result,, been quarantined or hospitalised. Many other parents and carers are unable to work due to lockdown or social distancing restrictions and, as a result, can’t afford food and other necessities.

The limitations of the emergency may mean, despite their best efforts, your organisation is unable to resolve these issues and assist the child to stay where they are until the emergency has passed and your organisation is able to return to their usual procedures. Large scale emergencies require creative responses and new ways of working.

Emergency Assessments: determining which living arrangements will be safest for the child

The aim of the emergency assessment process is to determine whether the child’s basic needs can be met where they are for the unknown period of COVID19 restrictions and, if not, where they would have the best chance of being safe.

This is a very limited assessment compared to what would be considered best practice under normal circumstances but still allows your organisation to gather the information needed to make a decision regarding the child’s immediate safety until the emergency abates, restrictions lift, and a full assessment can be conducted.

Methods for conducting assessments under restrictions.

Phone and video calls are valuable tools in emergency situations. Video calls might include someone doing a camera review of their house and both phone and video calls allow for interviews with everyone in the household.

For some of you, this won’t be a practical option. In those circumstances face to face visits must only take place subject to government advice, risk assessment of safety for the staff member (which must be prioritised), and only where absolutely necessary. In the current situation strategies need to be implemented to allow social distancing to take place.

If assessments cannot be completed then the placement should not go ahead as without a clear understanding of the situation you cannot be confident the child will be safe.

Emergency assessments should only be conducted if it has been determined a child cannot remain where they are. If this is not the case, assessments should be delayed until after the emergency when a full, best practice, process can be followed.

This might happen for the following reasons:

- The child is living in a children’s home that has been mandated to close by the government.

- The child is living in a children’s home that is trying to reduce numbers as a result of the emergency situation (in the current situation, this might be in an effort to improve social distancing and isolation option or as a result of low staff due to COVID-19 infections or exposure.

- The child is living in the community in an unsafe family.

- The child is living in the community in a family that is unable to care for them as a direct result of the emergency (e.g. parents hospitalised due to COVID-19 infection).

The emergency assessment process is designed to help your organisation find a safe option that can temporarily care for the child during the emergency and until best practice assessment processes can resume.

Step One

- Is there a family member the child regularly visits that is considered safe (and is either known to you, the child or the family)?

- If you are working in a children’s home you will (hopefully) have this information (ideally it will be recorded in their care file. We are aware not all children’s homes have such files. If this is the case for your organisation, we would recommend setting up a clear case management system as soon as you are able after the emergency situation and be sure to keep careful records of any assessments conducted during the emergency period so they can be incorporated in the new system).

- If you do not know this information, or the child is living in the community, then it’s time to ask the family and the child.

There are several reasons we explore this option:

- It’s familiar (therefore the child is more likely to feel safe and be safe),

- it’s where a child already has a relationship (therefore the child feels a connection and a sense of belonging so are likely to feel safer),

- it meets their identity/cultural needs (provides for their emotional need to connect to themselves, their family and their environment),

- it involves minimal change (our brains prefer familiarity and the certainty that comes with it so feel safer when change is minimised).

If we think of a child’s main needs as physical and emotional safety – both being and feeling safe and a sense of belonging (connection to people, place and culture), then a home where they experience these things is where they have the best chance of thriving.

Therefore, If this first option can provide safe care, it is in the child’s best interest to move there.

Step Two

What if there is no information or no family member known or able to provide such care; or such options are impractical (too far away, for example)?

This is when we then need to explore the other options.

Formal Options

Are there any formal foster carers available? Are there any children’s homes (preferably small ones) that are regulated and you know are safe?

If yes, these might be viable options for a temporary solution as they provide you with an option that has been assessed as safe by a other organisation (the regulating body of the children’s homes or the organisation providing foster care.

But we need to check two things first:

.1. Do the assessments/inspections/reports from the other organisation satisfy us that the placement would be safe for the child and meet the child’s needs, especially if there are any disabilities?

(a) This is important as your organisation needs to ensure any child placed with a foster carer or a children’s home will not suffer abuse, neglect or have to move again. Never assume that a children’s home or formal foster care placement is going to be safe and appropriate.

(b) If you do not have assessments/inspections/reports you might use your own knowledge (or other people’s knowledge) of the organisation providing the care but you need to be confident that it will provide safe and appropriate care and this should only be done as a final resort if all other alternatives have been exhausted.

.2. Are there any better alternatives?

Informal Options

In emergency situations, organisations sometimes choose places for children to live that have not been through the standard full assessment procedure. This might be a family member who has not previously cared for the child but knows them, or might be a member of the community known to you or the family or someone community leaders know of who might be able to offer care to a child.

Keeping in mind the importance of belonging and connection, for the child a safe and appropriate placement with a family member, even if it is one they haven’t previously stayed with, is usually preferable to alternatives. However, conducting an assessment to ensure it will be a safe place for the child to live is still essential. This should be more in-depth than the one that would be completed if the child was to be placed with a family member they stay with regularly. In this case, the assessment will need to explore what they know of the child, their parenting experience, how they can meet the child’s needs, their motivation and more so you can assess if the placement is more likely than not to be safe and appropriate for a significant period of time.

Placement with a community member is more risky but is sometimes the best option. This type of placement requires an even more in-depth assessment, exploring the reasons why they want to do this, whether the child might be at risk of trafficking, abuse or slavery as well as the standard questions around parenting experience, how they will meet the child’s needs, and so on.

In the UK, Dan has placed a child with a neighbour who knew the child very well and was willing to care for them until we could conduct a full assessment of the situation.

In Uganda, Joseph has arranged for a local community member known to the CALM staff to become a temporary foster carer until they could conduct a full assessment and find a suitable, long-term arrangement.

In both scenarios, checks must be made with police and community leaders and you need to consider how practical it is for your organisation to monitor the placement. Remember that checks need to include everyone in the household and assessments should involve talking to everyone in the household.

Informal options provide a higher level of risk as we know the least information about the people and homes involved but they could still provide a safe option for the child.

In all situations, emergency assessments need to take into account any visitors to the home as well as other homes the family might visit for overnight stays. Initial steps can include asking the family not to have overnight guests or stay overnight elsewhere until a time where more thorough assessments can be completed.

Monitoring of the Child to Ensure Safety during Large Scale Emergencies

It is vital that children living in the community and in children’s homes are monitored to ensure they are safe.

Monitoring normally involves visiting the child and talking to them face to face. However, in the case of a wide spread emergency situation like the current pandemic you may be limited to phone or video calls. Monitoring could involve texts/whatsapp or other sources. As children may not be able to talk freely it might be useful to set up codewords prior to their move to the new living situation for them to use to indicate they are not safe.

Just as during non emergency periods, the frequency of monitoring visits or calls will vary according to the needs and vulnerabilities of the child and the placement. In informal options, such as a family or community member, the child doesn’t normally visit checks should be daily or every other day for the first month and then reviewed but never less than once a week. In other situations it should be a minimum of once a week and more frequent in the first month (every other day).

If possible ask trusted community leaders or community members to also check in by phone calls, distance observations (walk by the home if safe to do so and within government guidelines) etc.

What if there is a concern about the child’s safety in the placement?

This will need to be carefully managed with government officials and processes for child protection but steps may include increased calls and checks and support. If in doubt, the child may need to move to another safe place. We will be discussing this in more detail in a future post.

What if calls are difficult?

Consider your options for providing carers with prepaid SIM cards or a basic phone at beginning of placement if possible. If phone access or other forms of contact and monitoring are going to be impossible to conduct safely, then you will need to review whether or not the placement can go ahead.

Analysis: deciding which placement is best

When we are deciding between placements we need to consider a number of factors.

Which one:

- is going to provide the safest level of care?

- is the more practical in terms of monitoring?

- is the placement we have the most information about?

- is the placement best suited to meet the child’s needs and causes the child the least disruption (eg geographical changes, family connection etc)?

It may be in a child’s best interest to remain in a children’s home. When exploring if a child can live elsewhere the conclusion may be that they could be safer in the home and the risks are too great or uncertain for you to be satisfied they can go elsewhere.

A word of caution: Never assume any placement option is safer than another. Every option must be properly assessed in order to make an informed decision based on the needs of the individual child.

During the COVID-19 pandemic (and in other emergency situations), for some children, remaining in a children’s home that is safe, providing food, access to water, preventing visitors, has toilets, has carers and is taking steps to provide extra care to minimise risk of infection may be a safer and more appropriate alternative than an emergency placement or move into the community in a rushed process. As circumstances improve and a full assessment can be conducted, that child’s placement in the home can be properly reviewed and alternatives considered, if appropriate.

The priority always needs to be to ensure the child, you and your team are SAFE.

What happens next? Some things to consider

When COVID19 restrictions are lifted, or the emergency eases, you can explore whether any emergency placements you have made could become more long-term or even permanent. Before making these decisions, more in-depth assessments would need to be conducted. If you’re interested in finding out more about how to do this, please use the form on our Contact page to get in touch.

Emergency situations, like the COVID-19 pandemic, often expose holes in our processes or problems with our normal way of working. Taking time after the emergency to reflect on what worked, what didn’t and what, if any systems, your organisation could have had in place beforehand that would help you, both in a large scale emergency and in your day to day practice, can lead to important steps towards best practice and providing the highest quality care and protection to the children you’re responsible to.

We hope this is a helpful starting point for you. Everything outlined here will need adapting to your context, culture, legislation, resources, government guidance and restrictions and it is not the only way of doing things. It’s an idea and framework to support your responses.

As the emergency resolves you and your organisation can continue on your journey towards ensuring the way you work is best practice but, for now, the focus is on safe practice.

Hang in there!

And remember, good enough really is good enough.

Sign Me Up for the Free Booklet!

Pingback: SFAC News In Brief - Vol 1 (May 2020) - SFAC